Neue Wilden Works from the 80s

The exhibit explores the early 80s, when Szczesny emerged as one of the protagonists of a young generation of bold figurative painters in the German-speaking world who came to be known as “Neue Wilde.” Contact the gallery for more information.

Modernism In The Service Of The Pleasure Principle: Stefan Szczesny’s Art by Donald Kuspit

Boldly self-conscious, and confrontational, in his two Self-Portraits of 1984 Stefan Szczesny presents himself as the classical Expressionist painter: passionate and rebellious, as the historian Douglas Kellner put it, a sort of transgressive Übermensch, as he adds, superior to the bourgeois “herd” by reason of his creativity, symbolized by the brush and palette he holds in one of the self-portraits. In that same self-portrait he is flanked by the sketch of a female nude and a more sedate female head, the former suggesting the body and the latter the soul of the Eternal Feminine, as Goethe called her, that “draws us on,” as he said at the end of Faust. The former is erotically romantic, her body there for the sexual asking, facing us in unashamed nakedness, the latter peculiarly remote and “classical,” a detached, insular profile, a woman with a mind of her own, unlike the odalisque, who seems all body and no mind. The contour of the odalisque’s young body is blue, the profile of the more mature woman is spotted with blue, but both are luminously white, suggesting they’re ghosts.

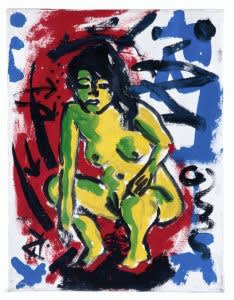

Indeed, they haunt Szczesny’s art, recurring with obsessive regularity, complementing each other, even oddly one: the eternal feminine, in all her indulgent nakedness, may be physically accessible, but she is emotionally inaccessible, strangely indifferent to the male artist’s penetrating gaze. She is, after all, eternal, that is, above it all, however seductively feminine and earthy her body may be. The point is made clear by the Blue Nude and Yellow Nude, both also painted in 1984—wonderful tributes, not to say idealizing homages to the Fauvist nudes of Matisse and the Brücke nudes of Kirchner. The blue nude is turned away from us, the yellow nude faces us, but she looks downward, with a kind of contemplative melancholy. Both seem unaware of the artist’s presence, although he’s clearly present in the Blue Nude.

Szczesny is excited by their bodies, as the flurry of painterly activity around them—dramatically black, with the yellow nude framed by an amorphous blur of passionate red—strongly suggests, but they couldn’t care less. He looks intensely at her in the Blue Nude, an intensity which spills over into the painterliness, but she turns away, and the contours of her body are intact, suggesting that she’s self-contained and impenetrable, making her mysterious for all the vividness of her flesh. The feminist historian Carol Duncan famously argued that the paintbrush was a surrogate phallus, but however powerful the expressionist painter’s handling it was unable to penetrate the female subject’s naked body, spilling its painterly seed over it in a futile attempt at intercourse. Duncan’s interpretation is somewhat extreme, but the point remains: the expressionist painter “manhandles” the female model’s body all he wishes, but his wish is never consummated, reminding us that expressionist paintings of the female nude are dreams, that is, surrogate wish fulfillments, as Freud said a dream is.

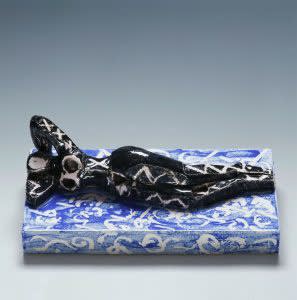

Let us recall that Faust sold his soul to the devil for sex—and his mind, for he was a great scholar and intellectual—but in the end was saved by a heavenly chorus. He wanted wealth and power, and finally married Venus, and had a family with her, but none of it gave him lasting pleasure. Nonetheless, his “striving” saved him, especially when it led him to reclaim land from the sea in the Netherlands, sublimating his instincts and thus recovering his reason. Striving is self-evident in Szczeny’s paintings—rational striving for aesthetic fulfillment, not just irrational striving for sexual fulfillment. Szczesny’s art may be erotomanic, but it also shows a great deal of aesthetic intelligence. His bust of a female nude epitomizes his obsession with woman in all her perverse majesty, but it is also an artistic tour de force, a pure work of art epitomizing modernist ideas about art. It may celebrate woman, but in the end more importantly it successfully brings together two basic strands of modernism: the emphasis on the medium for its own material sake, as Clement Greenberg put it, and the attempt to articulate what Kandinsky called the “dissonance” and “discontinuity” of modern life, involving the seemingly insurmountable conflict between the material and spiritual, in the “dynamic equilibrium”—ironic harmony?–of a “new (visual) music.” The bust is a consummate, masterly realization of these two goals.

The vivid colors—the familiar red and black–with their vigorous handling, clash and contrast, adding an expressionistic surface to the classical bust, seemingly made of pure white light, but they also bizarrely harmonize, as they do in an all-over painting. There may be reckless abandon in the painterliness, but the extravagant gestures, seemingly straight from the unconscious, form a self-conscious whole. The seemingly uncontrollable, “wild” gestures—reminding us that Szczesny was one of the major painters in the German Neue Wilden movement that emerged into international prominence with the “New Spirit of Painting” exhibition held in Berlin and London in 1981—are in fact under complete aesthetic control. The colorful surface is in effect a pure painting—painting for the sake of painting, aesthetically refining raw pigment, giving it what the materialistic Greenberg himself called “unconscious and preconscious” meaning, borrowing the terms from the topographical model of the psyche that Freud described in The Interpretation of Dreams. Similarly, Szczesny integrates two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture, making for a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. Dynamic painting is in effect three-dimensionalized, adding to the projective power of the color, and static sculpture two-dimensionalized into a canvas that becomes a kind of cornucopia of color. Szczesny’s painted sculptures are aesthetically profound, for they reconcile the opposites by emphasizing their opposition.

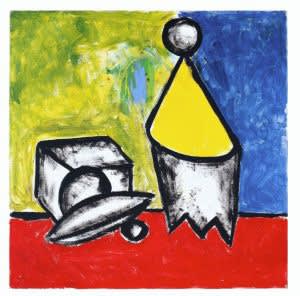

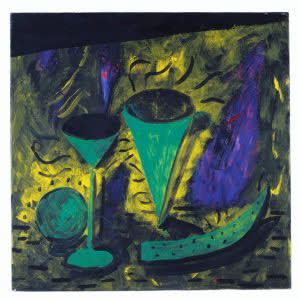

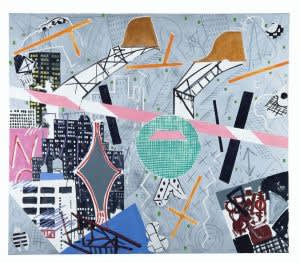

The bust is a kind of dialectical masterpiece. Once Szezesny abandons the equivocally eternal feminine, and turns to the even more equivocal—relentlessly contradictory—modern world, as he does in a number of urbanscapes, he comes into his dialectical own. In Noratlas, 1980 a diagonal cuts across fragments of urban space, reminding us, as Theodor Adorno emphasized, that modern art is a sum of fragments rather than a preconceived whole, like the modern world and unlike traditional art. The work evokes Malevich’s Aerodynamic Suprematism—the first phase of Suprematism–thus taking us back to the abstract beginnings of modern art and its fascination with modern technology. The two airplane fragments seem to have a direct predecessor in Gorky’s 1937 design for a mural—now painted over–at Newark airport. The black diagonal cutting through an untitled urbanscape conveys the dynamics of the city and the jumble of fragmentary building facades its unsettling energy—an energy evident everywhere in Szczesny’s art. It is concentrated in the objects in his wonderful still lives. Shedding the eternal feminine, Szczesny comes into his masculine own: his objects have a geometrical sturdiness, solidity, and solemnity—the objects in one still life allude to Cézanne’s idea that painters should “treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone” (in effect eternalizing nature)–that his curvaceous, exciting females lack, perhaps because they are the objects of desire rather than objects that have what the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott called the indisputable separateness of reality.

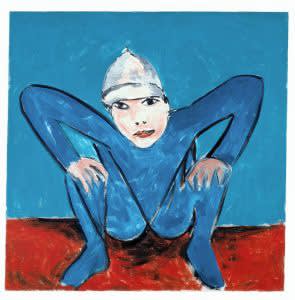

Szczesny’s David, 1984, a deceptively simple portrait—certainly less busy, or at least more restrained and straightforward than many of Szczesny’s works–of his young son, crouching with his hands on his knees, is another “objective” masterpiece, as the eternalizing geometry of his body—his triangular torso, flanked by curved buttocks—makes clear. Abstraction and representation ingeniously converge, even as they remain at odds, making the figure uncanny. Szezesny “argues” for their inseparability–the aesthetic necessity of both—but the tension between them is excruciating, suggesting their inherent difference. Their simultaneity confirms their estrangement even as it unites them. Apollinaire famously said that “the simultaneity of colors through simultaneous contrasts and through all the quantities that emanate from the colors, in accordance with the way they are expressed in the movement represented…is the only reality one can construct through painting,” but Szczesny shows that this is not exclusively so. The simultaneity of colors can also be used to “construct” human reality, however autonomous and “self-serving” they remain: quantity can become quality. David’s confrontational pose and intense wide-eyed stare–set in a face that harks back to the mask-like “primitivized” faces in Matisse’s portraits of his son—suggest that he’s a Neue Wilden in the making.

The conflict between the blue and red suggests his inner conflict: the dialectic of his being is unresolved. Primary colors are always at odds, however reconcilable in complementary colors, but there are no complementary colors in Szczesny’s painting, making it even more starkly expressive. It brings to mind Kirchner’s Seated Girl, 1910—she’s as defiant as David–but it has orange, yellow, and green it, compromising the strong red and blue planes. They are uncompromisingly in-your-face in Szczesny’s portrait. They are more dramatically insistent than in any expressionist portrait. Once again blue represents reason, red represents instinct, which are perennially at odds, but they make powerful aesthetic and emotional music together in Szczesny’s masterpiece.